December

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, et al. The Sorrows of Young Werther and Selected Writings. Signet Classics, 2013. First published in German 1774.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, et al. The Sorrows of Young Werther and Selected Writings. Signet Classics, 2013. First published in German 1774.

Doyle, Arthur Conan. The Hound of the Baskervilles. Dover, 1994. (First published 1902).

Doyle, Arthur Conan. The Hound of the Baskervilles. Dover, 1994. (First published 1902).

Levi-Strauss, Claude. The Savage Mind. Univ. of Chicago Press, 2010. (First published 1962)

Levi-Strauss, Claude. The Savage Mind. Univ. of Chicago Press, 2010. (First published 1962)

Eco, Umberto (translated by William Weaver). The Name of the Rose. Pan, 1984. (First published 1980).

Cobley, Paul, and Litza Jansz. Introducing Semiotics. Icon Books Ltd, 2012.

November

Polo, Marco, Rustichello da Pisa, John Frampton (translator) and Milton Rugoff. The Travels of Marco Polo. Signet Classics, 2004. (published c. 1300).

Polo, Marco, Rustichello da Pisa, John Frampton (translator) and Milton Rugoff. The Travels of Marco Polo. Signet Classics, 2004. (published c. 1300).

Orwell, George. Why I Write. Penguin Books, 2005. (first edition 1946).

Orwell, George. Why I Write. Penguin Books, 2005. (first edition 1946). Morin, Amy. 13 Things Mentally Strong People Don’t Do: Take Back Your Power, Embrace Change, Face Your Fears and Train Your Brain. William Morrow, 2015.

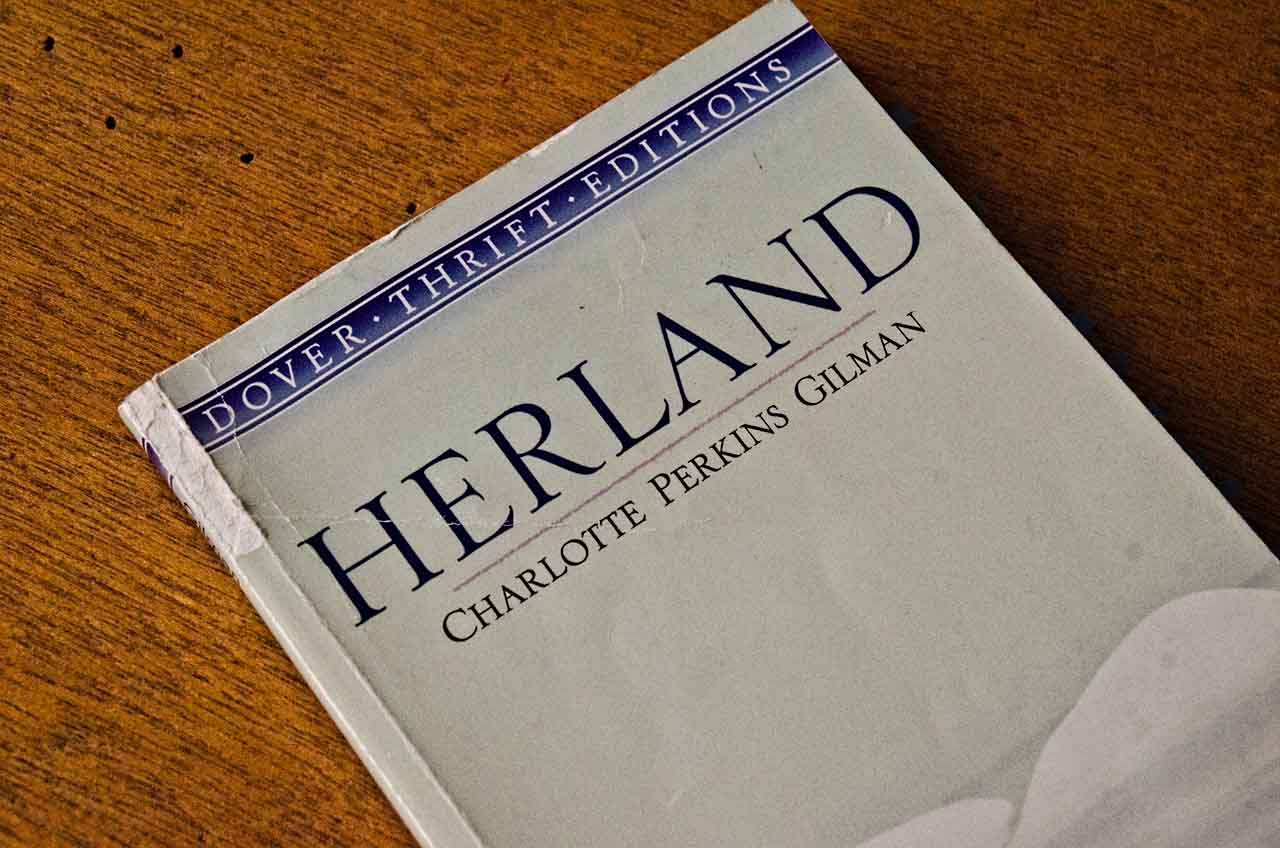

Morin, Amy. 13 Things Mentally Strong People Don’t Do: Take Back Your Power, Embrace Change, Face Your Fears and Train Your Brain. William Morrow, 2015. Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. Herland. Dover Publications, 1998. (published as a serial 1915, first published 1979).

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. Herland. Dover Publications, 1998. (published as a serial 1915, first published 1979).

October

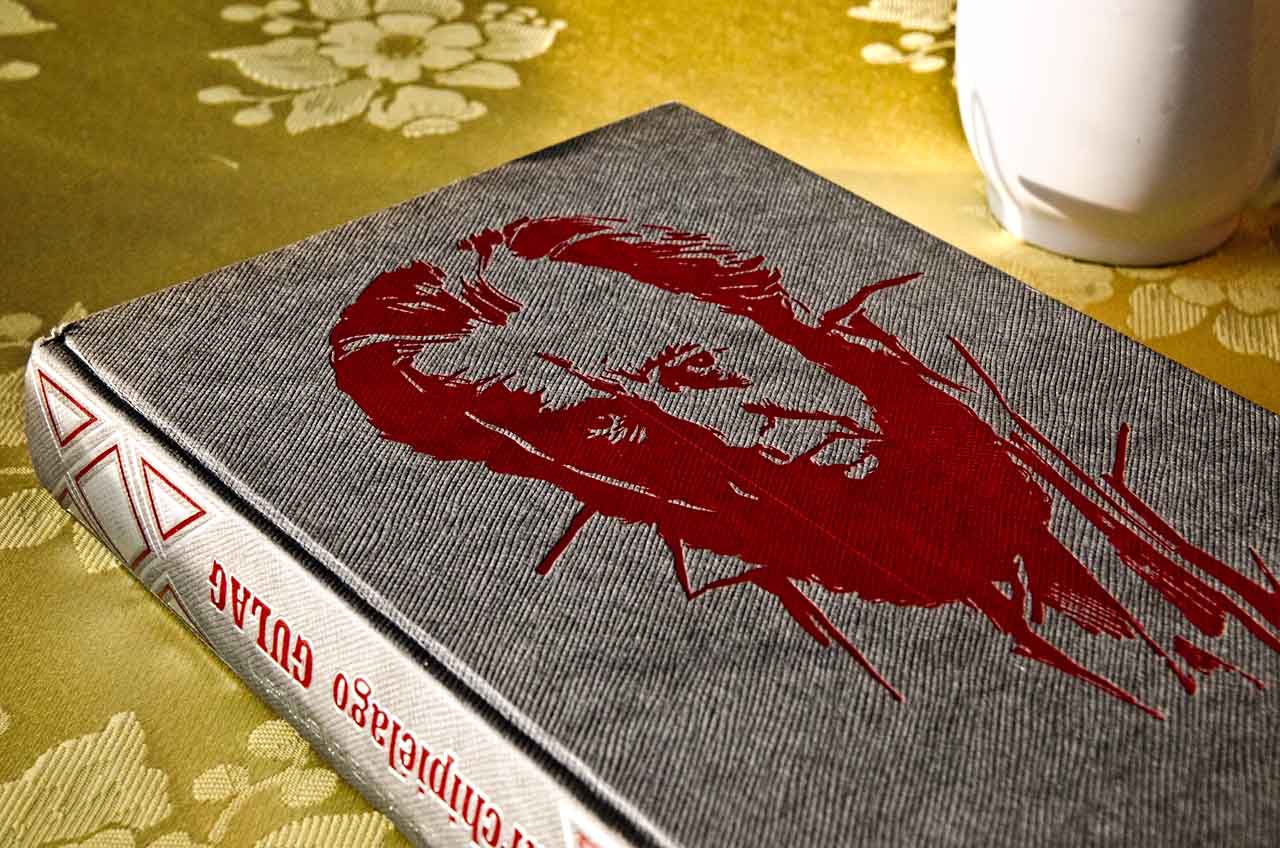

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr (traducida al español 1975 ). Archipiélago Gulag. 1973.

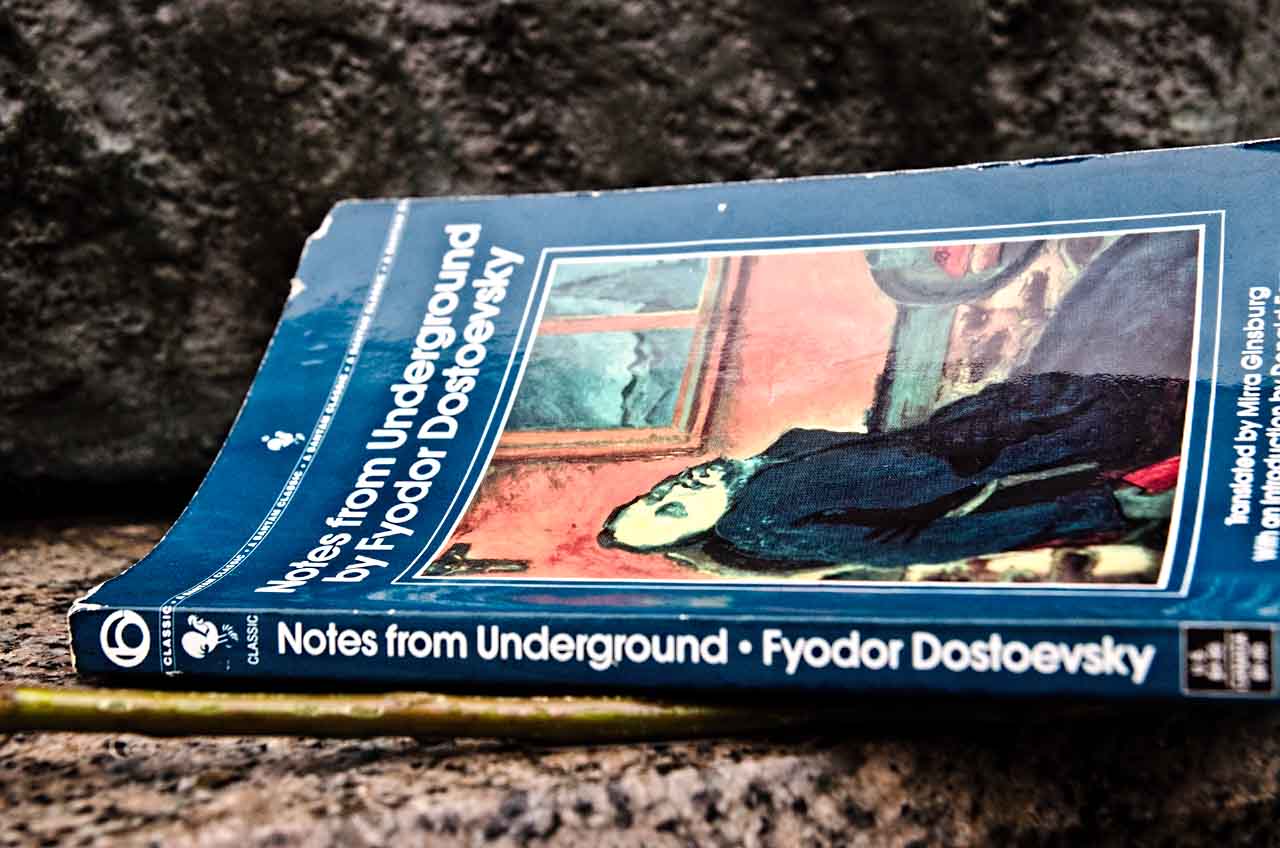

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr (traducida al español 1975 ). Archipiélago Gulag. 1973.  Dostoyevsky, Fyodor (translated by Mirra Ginsberg, 1974). Notes from Underground. 1864.

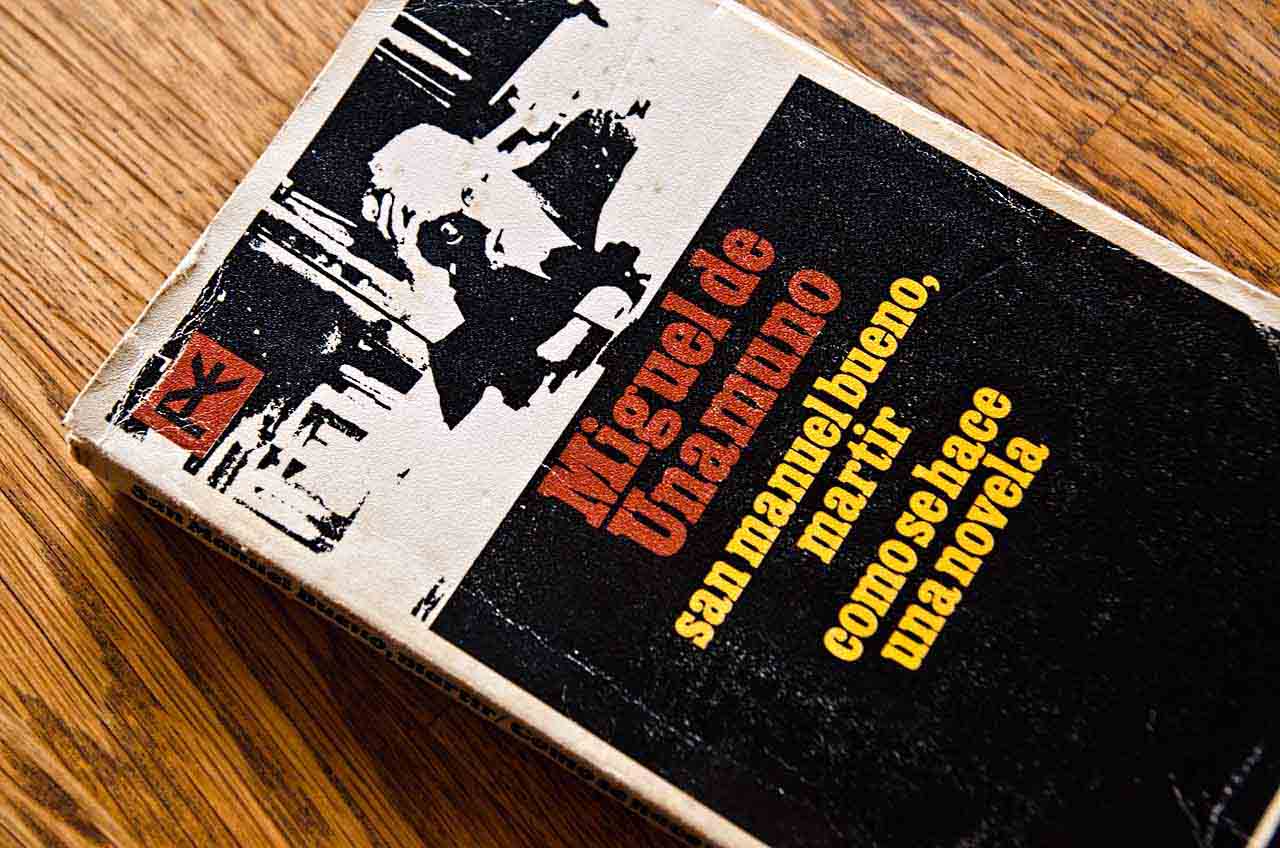

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor (translated by Mirra Ginsberg, 1974). Notes from Underground. 1864. Unamuno y Jugo, Miguel de. San Manuel Bueno, mártir. 1931.

Unamuno y Jugo, Miguel de. San Manuel Bueno, mártir. 1931.

Unamuno y Jugo, Miguel de. Cómo se hace una novela. 1927.

September

Saramago, José. Blindness. 1995.

Saramago, José. Blindness. 1995.

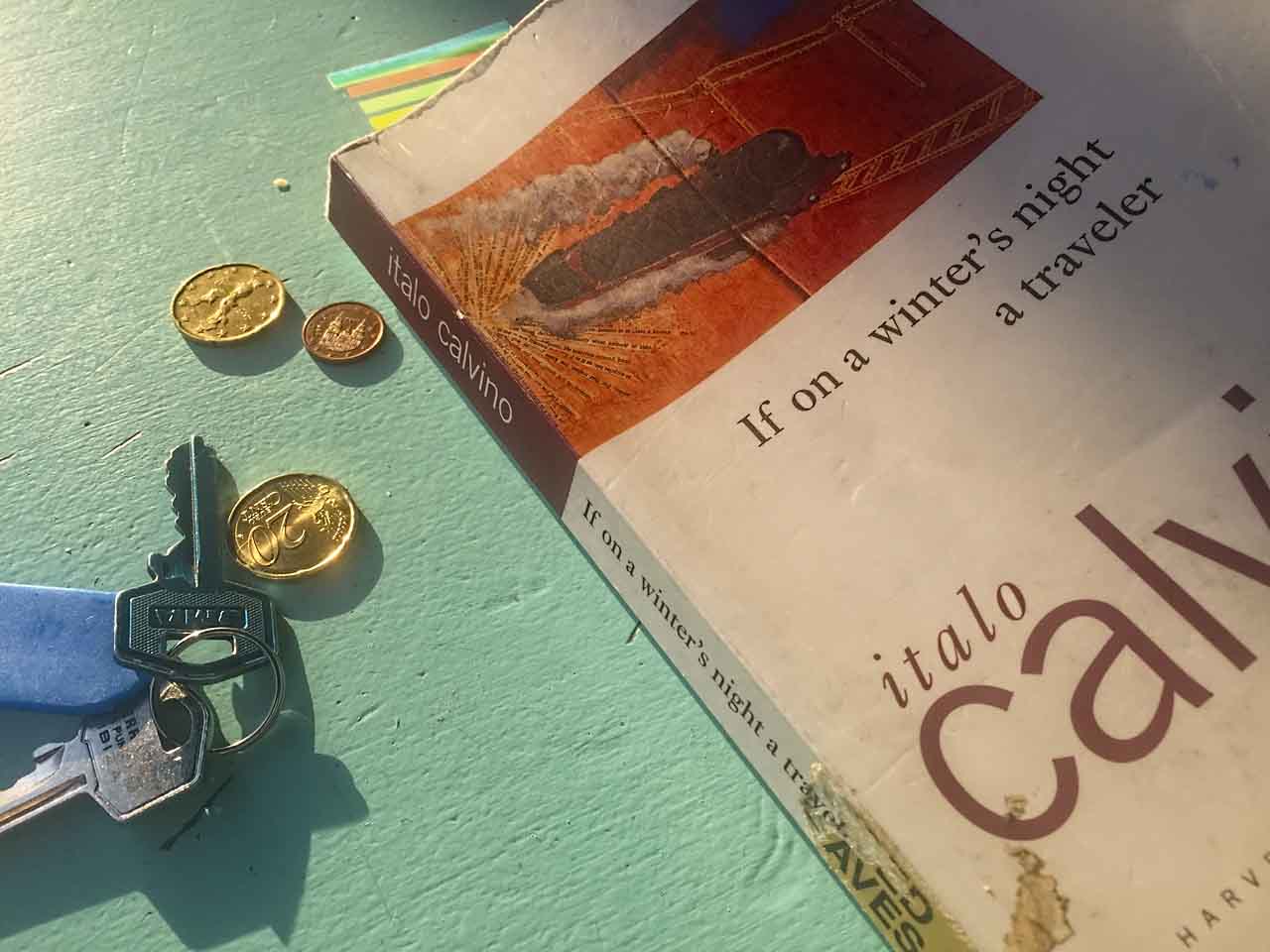

Calvino, Italo. If on a winter’s night a traveler. 1979. (Translated by William Weaver, 1981).

Calvino, Italo. If on a winter’s night a traveler. 1979. (Translated by William Weaver, 1981).

August

Jung, C. G., and Marie-Luise von Franz. Man and His Symbols. Dell, 1964.

Jung, C. G., and Marie-Luise von Franz. Man and His Symbols. Dell, 1964.

Laozi, translated by Tolbert McCaroll. Tao Te Ching. China: 4th Century BC. (First translated to English 1868)

Laozi, translated by Tolbert McCaroll. Tao Te Ching. China: 4th Century BC. (First translated to English 1868)

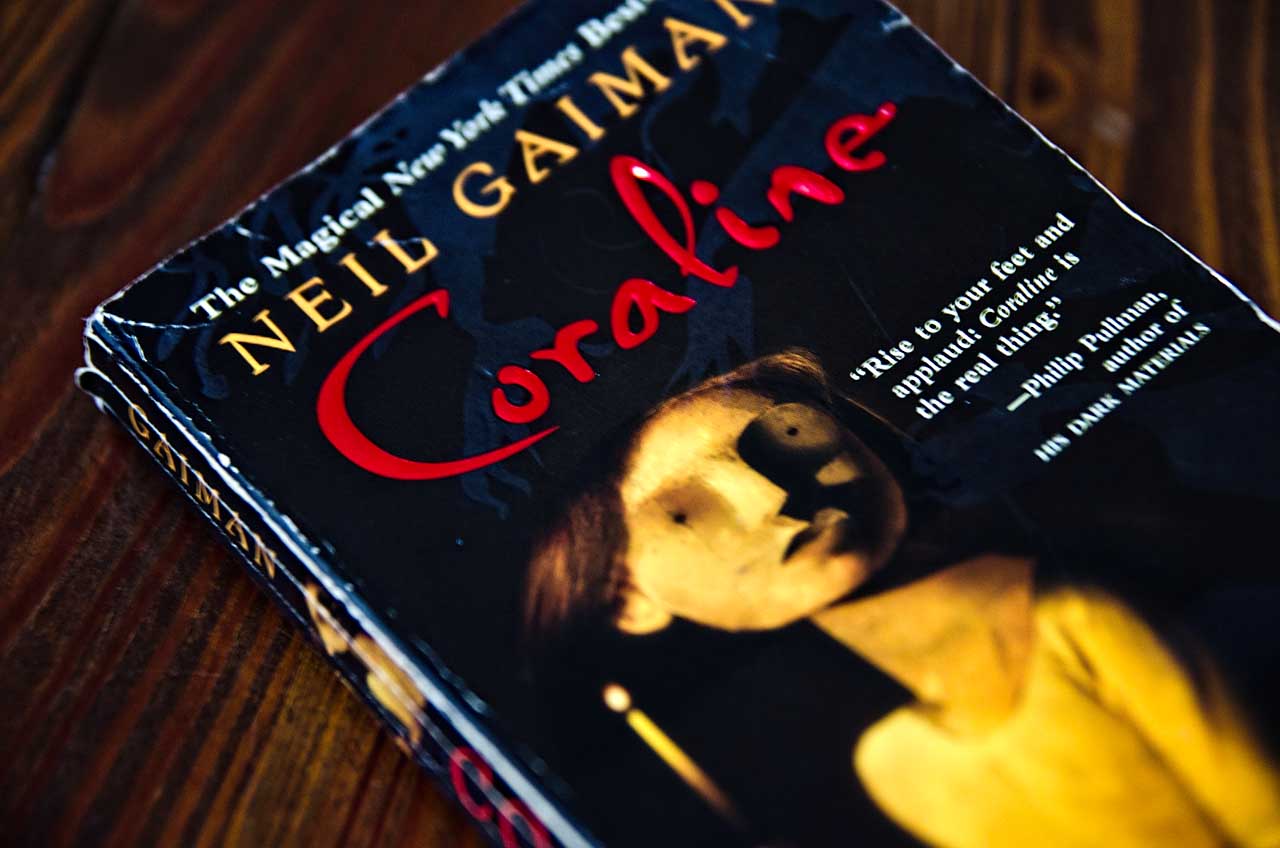

Gaiman, Neil, and Dave McKean. Coraline. HarperCollins, 2002.

Gaiman, Neil, and Dave McKean. Coraline. HarperCollins, 2002.

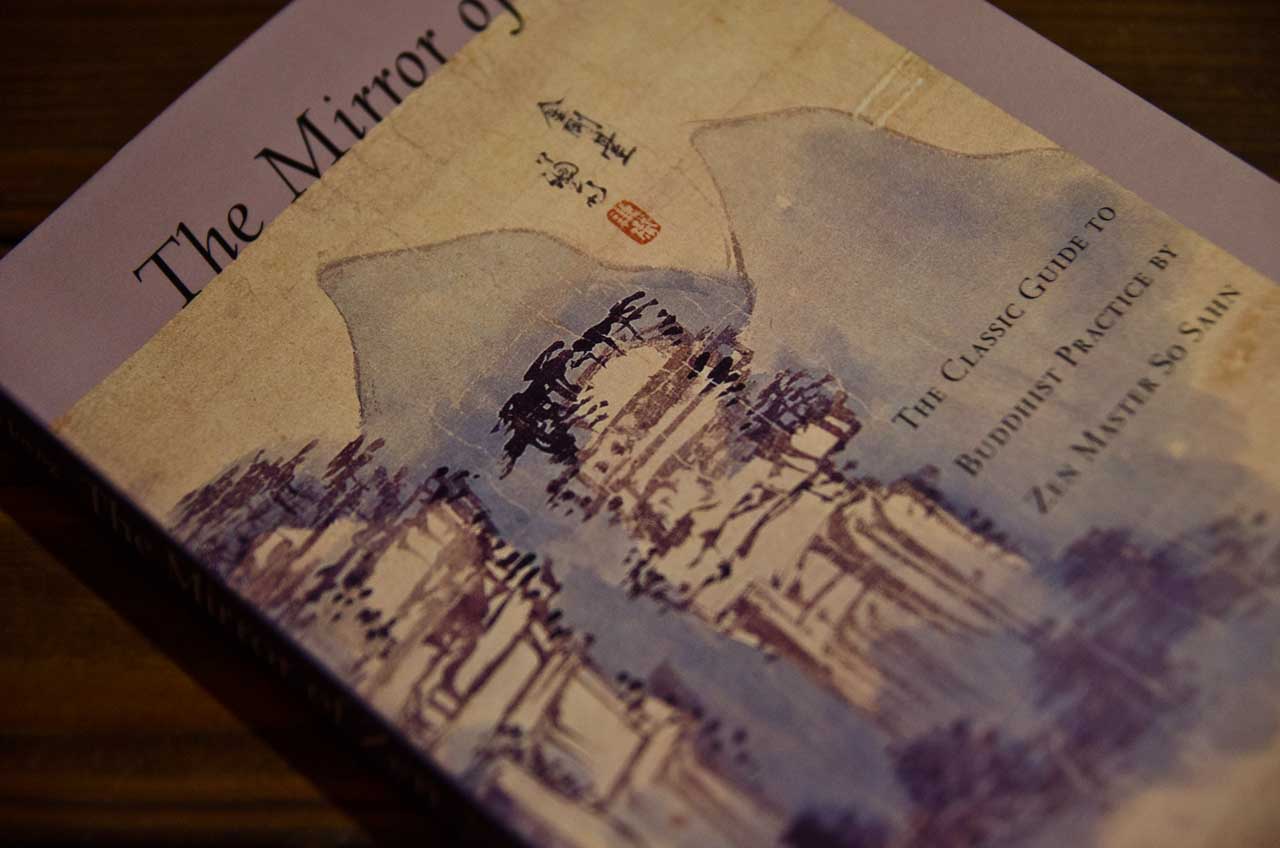

HyoÌngÌak, et al. The Mirror of Zen: the Classic Guide to Buddhist Practice by Zen Master So Sahn. Shambhala, 2006.

HyoÌngÌak, et al. The Mirror of Zen: the Classic Guide to Buddhist Practice by Zen Master So Sahn. Shambhala, 2006.

July

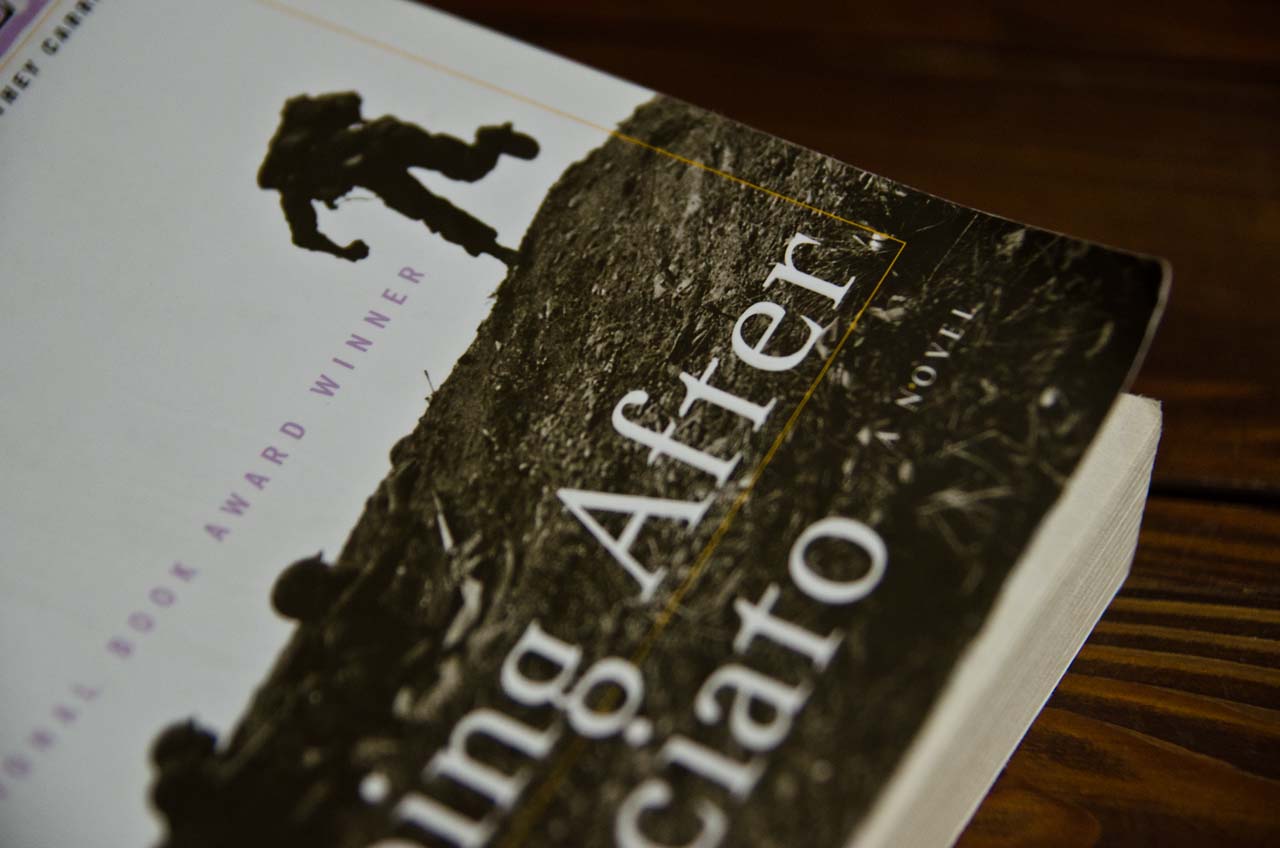

O’Brien, Tim. Going after Cacciato. Broadway Books, 2014. First published 1978.

O’Brien, Tim. Going after Cacciato. Broadway Books, 2014. First published 1978.

Card, Orson Scott. Ender’s Game. Starscape, 2011. First published 1985.

Card, Orson Scott. Ender’s Game. Starscape, 2011. First published 1985.

Kafka, Franz, and Stanley Corngold. The Metamorphosis. Bantam Classic, 2004. First published 1915.

Kafka, Franz, and Stanley Corngold. The Metamorphosis. Bantam Classic, 2004. First published 1915.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm, and Graham Parkes. Thus Spoke Zarathustra: a Book for Everyone and Nobody. Oxford University Press, 2008. First published 1883–1891.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm, and Graham Parkes. Thus Spoke Zarathustra: a Book for Everyone and Nobody. Oxford University Press, 2008. First published 1883–1891.

Hesse, Hermann, and Sherab ChoÌdzin. Kohn. Siddhartha. Boston, Massachussets: Shambhala Publications, 2005. Print. First published 1922.

Hesse, Hermann, and Sherab ChoÌdzin. Kohn. Siddhartha. Boston, Massachussets: Shambhala Publications, 2005. Print. First published 1922.

Grimm, Jacob, Neil Gaiman, Lorenzo Mattotti, and Wilhelm Grimm. Hansel & Gretel: A Toon Graphic. New York, NY: Toon, 2014. Print.

Grimm, Jacob, Neil Gaiman, Lorenzo Mattotti, and Wilhelm Grimm. Hansel & Gretel: A Toon Graphic. New York, NY: Toon, 2014. Print.

June

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Birth of Tragedy. New York: Double Day Anchor, 1956. Print. Translated by Francis Golfing. First published 1872.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Birth of Tragedy. New York: Double Day Anchor, 1956. Print. Translated by Francis Golfing. First published 1872.

Lessing, Doris. On Cats. London: Harper Perennial, 2008. Print. First published 2002.

Lessing, Doris. On Cats. London: Harper Perennial, 2008. Print. First published 2002.

Camus, Albert. The Outsider. London: Penguin Modern Classics, 1982. Print. Translated by Joseph Laredo. First published 1942.

Camus, Albert. The Outsider. London: Penguin Modern Classics, 1982. Print. Translated by Joseph Laredo. First published 1942.

Carnegie, Dale. How to Win Friends & Influence People. New York: Pocket, 1982. Print. First Published 1936.

Carnegie, Dale. How to Win Friends & Influence People. New York: Pocket, 1982. Print. First Published 1936.

May

Orwell, George. 1984. New York: Signet Classic, 1984. Print. First published 1949.

Orwell, George. 1984. New York: Signet Classic, 1984. Print. First published 1949.

Pirie, Madsen. How to Win Every Argument: The Use and Abuse of Logic. Bloomsbury Academic: Continuum, 2010. Print.

Pirie, Madsen. How to Win Every Argument: The Use and Abuse of Logic. Bloomsbury Academic: Continuum, 2010. Print.

Jelinek, Elfriede, and Joachim Neugroschel. The Piano Teacher. New York: Grove, 2009. Print. First published 1983.

Jelinek, Elfriede, and Joachim Neugroschel. The Piano Teacher. New York: Grove, 2009. Print. First published 1983.

King, Stephen. On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. New York: Scribner, 2010. Print. First published 2000.

King, Stephen. On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. New York: Scribner, 2010. Print. First published 2000.

April

Corbusier, Le. Towards a New Architecture. Mineola, NY: Dover, 1986. Print. First edition 1931.

Corbusier, Le. Towards a New Architecture. Mineola, NY: Dover, 1986. Print. First edition 1931.

Chevrier, Yves. Mao and the Chinese Revolution. Moreton-in-Marsh, Gloucestershire: Arris, 2004. Print.

Chevrier, Yves. Mao and the Chinese Revolution. Moreton-in-Marsh, Gloucestershire: Arris, 2004. Print.

Morrison, Toni. Beloved. London: Vintage, 2010. Print. (First published 1987)

Morrison, Toni. Beloved. London: Vintage, 2010. Print. (First published 1987)

Kerouac, Jack. Big Sur. New York: Penguin, 1992. Print. First ed. 1962.

Kerouac, Jack. Big Sur. New York: Penguin, 1992. Print. First ed. 1962.

Aesop, and Jack Zipes. Aesop’s Fables. London: Penguin Popular Classics, 1996. Print.

Aesop, and Jack Zipes. Aesop’s Fables. London: Penguin Popular Classics, 1996. Print.

March

Silbiger, Steven. The Ten-day MBA: A Step-by-step Guide to Mastering the Skills Taught in America’s Top Business Schools. New York: Harpercollin, 2005. Print.

Silbiger, Steven. The Ten-day MBA: A Step-by-step Guide to Mastering the Skills Taught in America’s Top Business Schools. New York: Harpercollin, 2005. Print.

Branson, Richard. Screw It, Let’s Do It: Lessons in Life and Business. London: Virgin, 2009. Print.

Branson, Richard. Screw It, Let’s Do It: Lessons in Life and Business. London: Virgin, 2009. Print.

Coelho, Paulo, and Alan R. Clarke. The Pilgrimage: A Contemporary Quest for Ancient Wisdom. New York: HarperTorch, 2004. Print. First ed. 1987.

Coelho, Paulo, and Alan R. Clarke. The Pilgrimage: A Contemporary Quest for Ancient Wisdom. New York: HarperTorch, 2004. Print. First ed. 1987.

Kiyosaki, Robert T. Why “A” Students Work for “C” Students: And “B” Students Work for the Government. Scottsdale, AZ: Plata, 2013. Print.

Kiyosaki, Robert T. Why “A” Students Work for “C” Students: And “B” Students Work for the Government. Scottsdale, AZ: Plata, 2013. Print.

Gaiman, Neil, and Dave McKean. The Graveyard Book. New York: Harper, 2010. Print.

Gaiman, Neil, and Dave McKean. The Graveyard Book. New York: Harper, 2010. Print.

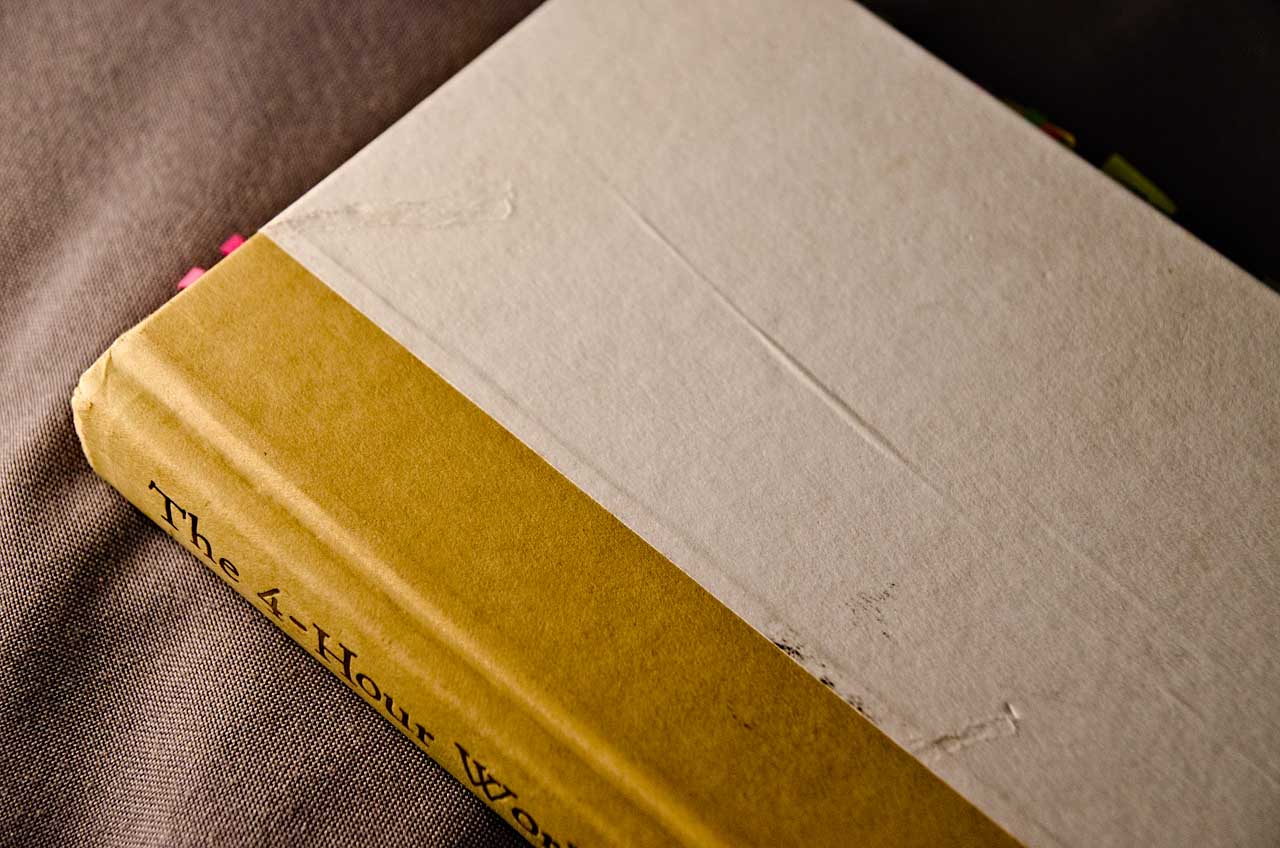

Ferriss, Timothy. The 4-hour Workweek: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich. New York: Crown Archetype, 2012. Print.

Ferriss, Timothy. The 4-hour Workweek: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich. New York: Crown Archetype, 2012. Print.

February

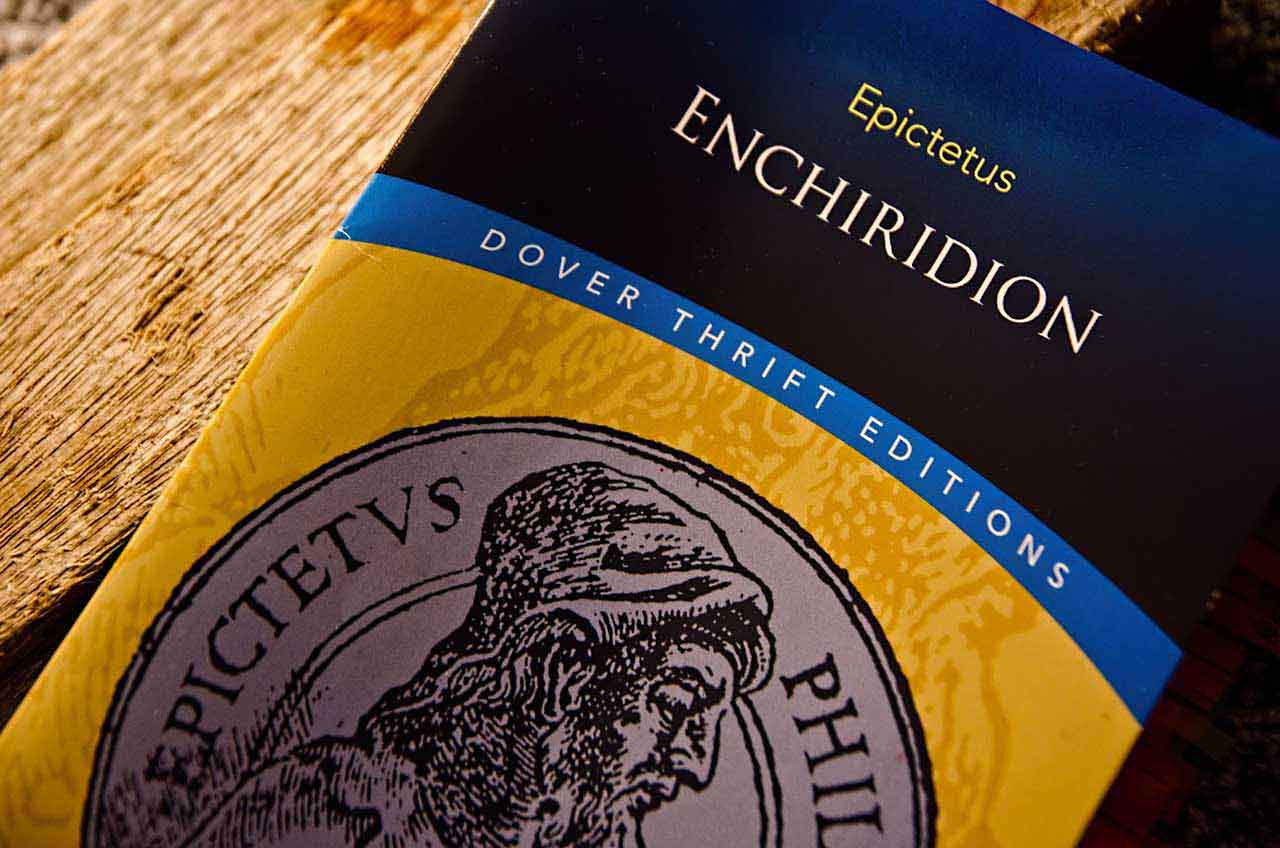

Epictetus, translated by George Long. Enchiridion. Mineola, NY: Dover Thrift, 2004. Print. First ed. 125 AD.

Epictetus, translated by George Long. Enchiridion. Mineola, NY: Dover Thrift, 2004. Print. First ed. 125 AD.

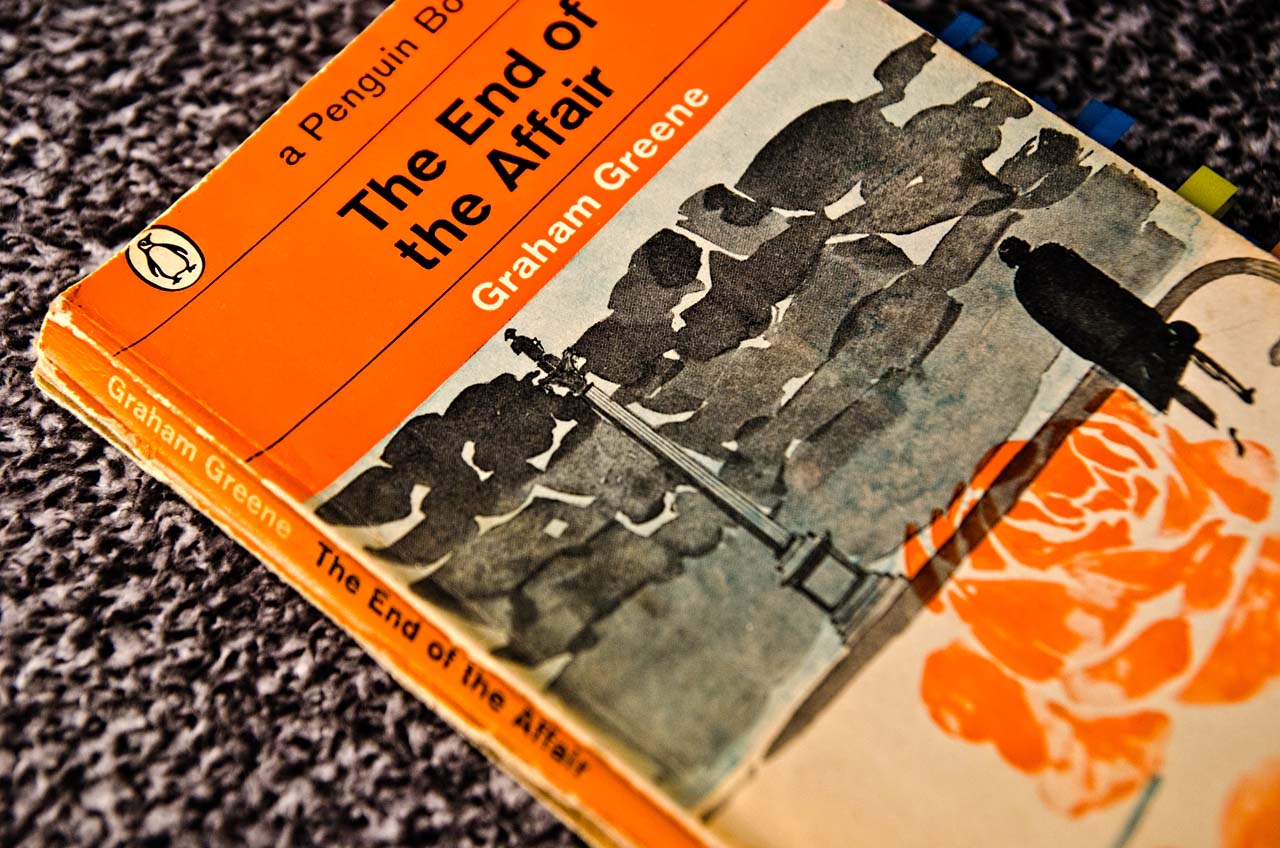

Greene, Graham. The End of the Affair. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1962. Print. First edition 1951.

Greene, Graham. The End of the Affair. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1962. Print. First edition 1951.

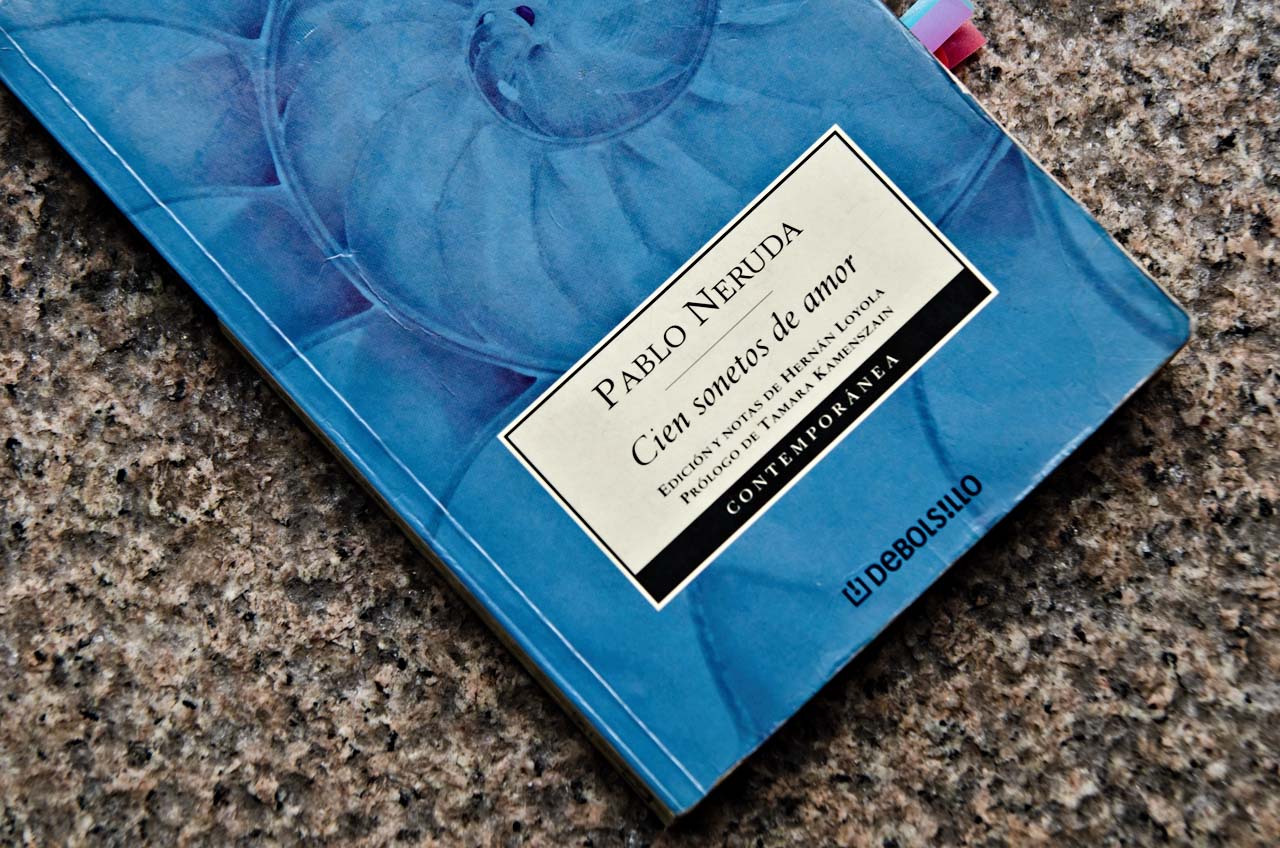

Neruda, Pablo., and Tamara Kamenszain, Cien sonetos de amor. Barcelona, España: Debolsillo, 2006. Print.

Neruda, Pablo., and Tamara Kamenszain, Cien sonetos de amor. Barcelona, España: Debolsillo, 2006. Print.

Thoreau, Henry David., and Michael Meyer. Walden and Civil Disobedience. NY: Penguin, 1983. Print.

Thoreau, Henry David., and Michael Meyer. Walden and Civil Disobedience. NY: Penguin, 1983. Print.

January

Giuttari, Michele, and Howard Curtis. A Death in Tuscany. London: Abacus, 2009. Print.

Giuttari, Michele, and Howard Curtis. A Death in Tuscany. London: Abacus, 2009. Print.

(I) Joyce, James. A Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man. New York: Bantam Books, 1992. Print. (First Edition 1916).

(I) Joyce, James. A Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man. New York: Bantam Books, 1992. Print. (First Edition 1916).

(V) Joyce, James. A Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man. New York: Bantam Books, 1992. Print. (First Edition 1916).

(I) Mackendrick, Alexander. On film-making: an introduction to the craft of the director. New York: Faber and faber, 2005. Print.

(I) Mackendrick, Alexander. On film-making: an introduction to the craft of the director. New York: Faber and faber, 2005. Print.

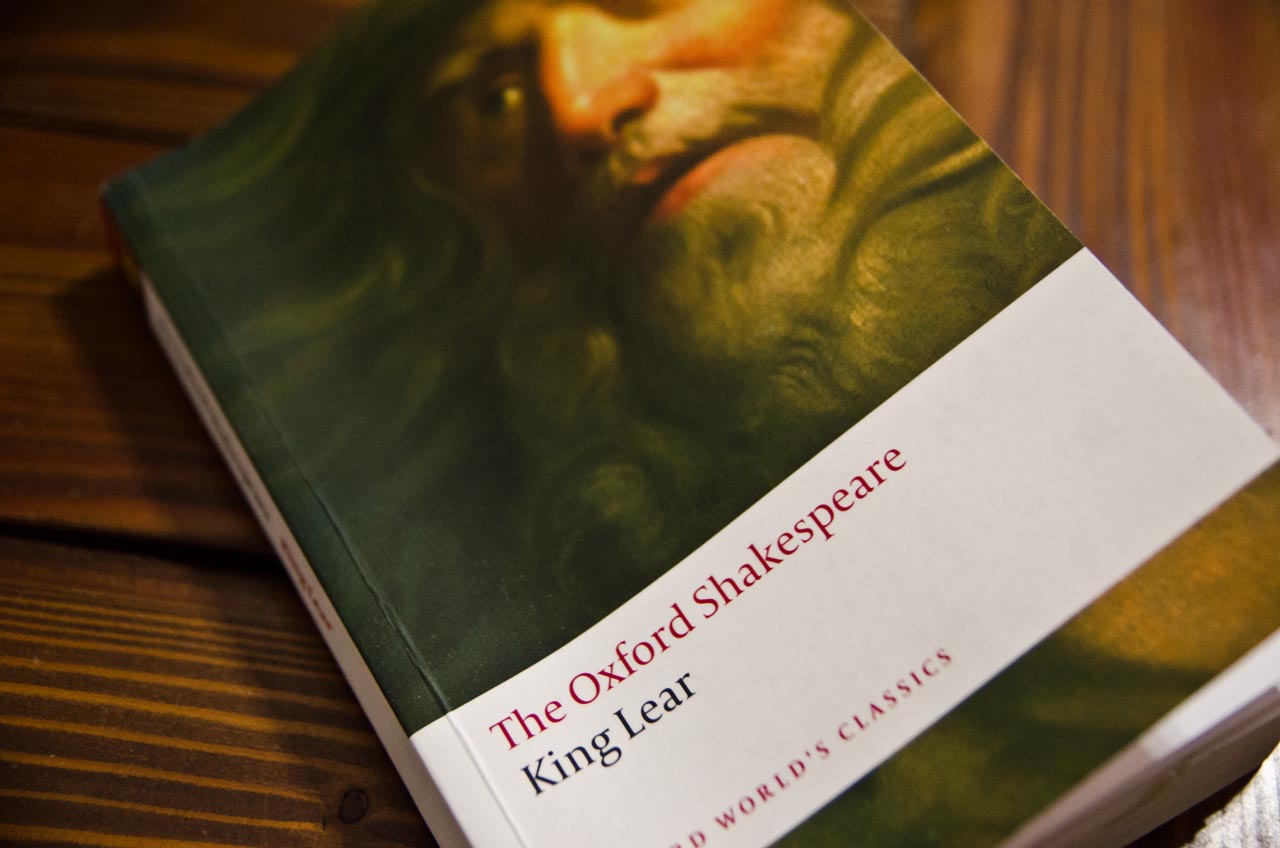

(I) Shakespeare, William, and Stanley Wells. The History of King Lear. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

(I) Shakespeare, William, and Stanley Wells. The History of King Lear. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

(II) Shakespeare, William, and Stanley Wells. The History of King Lear. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Wiesel, Elie, and Marion Wiesel. Night. New York, NY: Hill and Wang, a Division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006. Print. (First Ed. 1958).

Wiesel, Elie, and Marion Wiesel. Night. New York, NY: Hill and Wang, a Division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006. Print. (First Ed. 1958).

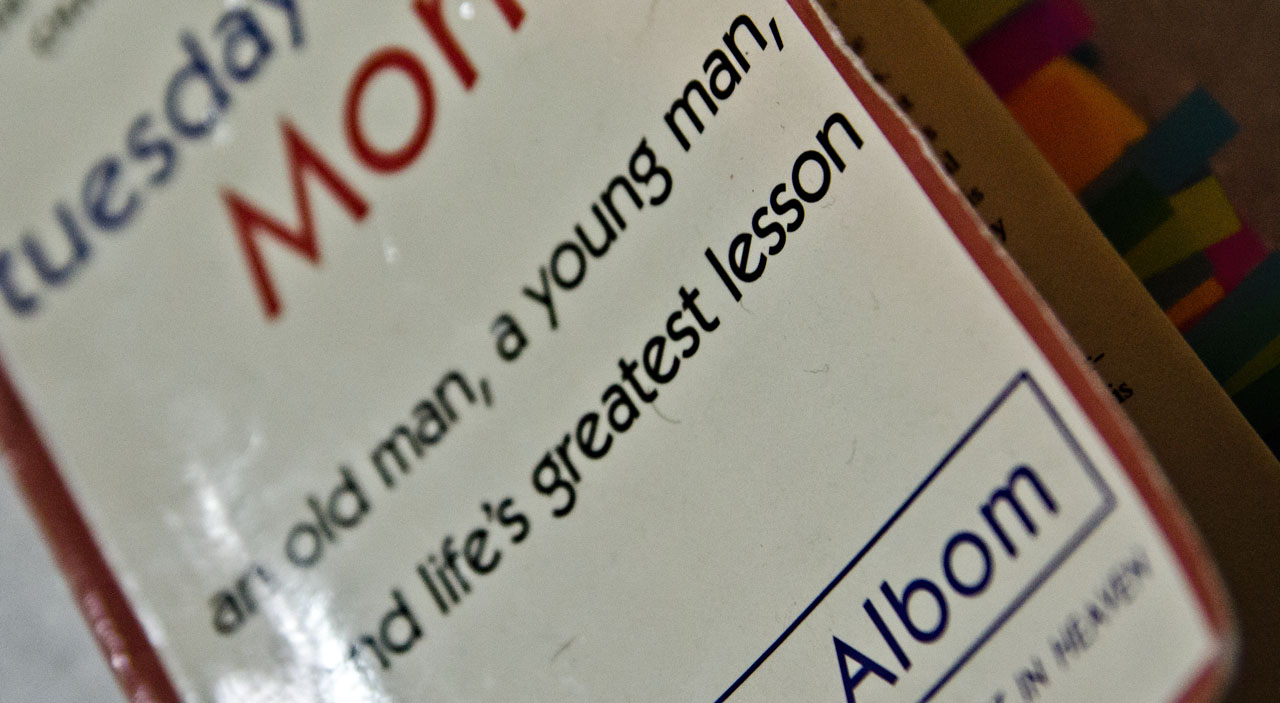

Albom, Mitch. Tuesdays With Morrie: an Old Man, a Young Man, and Life’s Greatest Lesson. New York: Anchor Books, 1997. Print.

Albom, Mitch. Tuesdays With Morrie: an Old Man, a Young Man, and Life’s Greatest Lesson. New York: Anchor Books, 1997. Print.