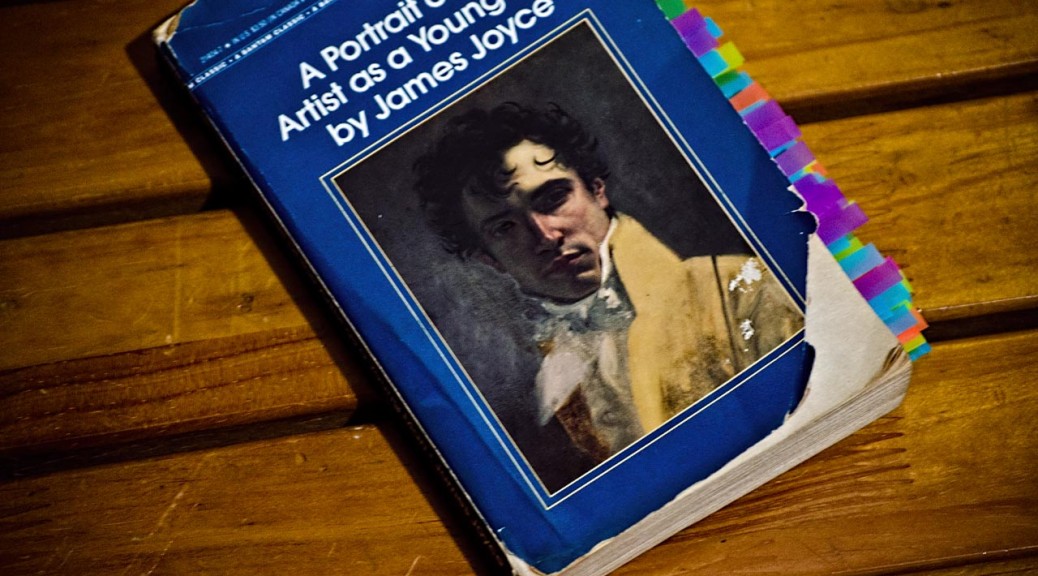

Joyce, James. A Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man. New York: Bantam Books, 1992. Print. (First Edition 1916).

—

To Read:

Finnegans Wake. 1939 (took Joyce seventeen years to write).

“Et ignotas animum dimittit in artes.” OVID, Metamorphoses, VIII., 18. (And he sets his mind to unknown arts) p. 1

“Then he heard the noise of the refectory every time he opened the flaps of his ears. It made a roar like a train at night. And when he closed the flaps the roar was shut off like a train going into a tunnel.” p. 7

“-Tell us, Dedalus, do you kiss your mother before you go to bed? Stephen answered:

-I do.

Wells turned to the other fellows and said:

-O, I say, here’s a fellow says he kisses his mother every night before he goes to bed.

The other fellows stopped their game and turned round, laughing. Stephen blushed under their eyes and said:

-I do not.

Wells said:

-O, I say, here’s a fellow says he doesn’t kiss his mother before he goes to bed.

They all laughed again. Stephen tried to laugh with them. He felt his whole body hot and confused in a moment. What was the right answer to the question?” p. 8

“But the Christmas vacation was very far away: but one time it would come because the earth moved round always.” p. 9

“There was a picture of the earth on the first page of his geography: a big ball in the middle of clouds. Fleming had a box of crayons and one night during free study he had coloured the earth green and the clouds maroon.” p. 9

“He turned to the flyleaf of the geography and read what he had written there: himself, his name and where he was.

Stephen Dedalus

Class of Elements

Clongowes Wood College

Sallins

County Kildare

Ireland

Europe

The World

The Universe” p. 10

County Kildare, Ireland

“What was after the universe? Nothing. But was there anything round the universe? Nothing. But was there anything round the universe to show where it stopped before the nothing place began? It could not be a wall but there could be a thin thin line there all round everything. It was very big to think about everything and everywhere. Only God could do that.” p. 10

Cork, Ireland.

“The corridors were darkly lit and the chapel was darkly lit. Soon all would be dark and sleeping. There was cold night air in the chapel and the marbles were the colour the sea was at night. The sea was cold day and night: but it was colder at night.” p. 12

“It would be lovely to sleep for one night in that cottage before the fire of smoking turf, in the dark lit by there fire, in the warm dark, breathing the smell of the peasants, air and rain and turf and corduroy. But, O, the road there between the trees was dark! You would be lost in the dark. It made him afraid to think of how it was.” p. 12

“The prefect’s shoes went away. Where? Down the staircase and along the corridors or to his room at the end? He saw the dark. Was it true about the black dog that walked there at night with eyes as big as carriagelamps? They said it was the ghost of a murderer. A long shiver of fear flowed over his body. He saw the dark entrance hall of the castle.” p. 13

“And the train raced on over the flat lands and past the Hill of Allen. The telegraph poles were passing, passing. The train went on and on. It knew. There were lanterns in the hall of his father’s house and ropes of green branches.” p. 14-15

See Fionn mac Cumhaill and the Fianna

Hill of Allen

***”Every rat had two eyes to look out of. Sleek slimy coats, little little feet tucked up to jump, black slimy eyes to look out of. They could understand how to jump. But the minds of rats could not understand trigonometry. When they were dead they lay on their sides. Their coats dried then. They were only dead things.” p. 16

“How pale the light was at the window! But that was nice. There fire rose and fell on the wall. It was like waves. Someone had put coal on and he heard voices. They were talking. It was the noise of waves. Or the waves were talking among themselves as they rose and fell.

He saw the sea of waves, long dark waves rising and falling, dark under the moonless night. A tiny light twinkled at the pierhead where the ship was entering: and he saw a multitude of people fathered by the water’s edge to see the ship that was entering their harbour.” p. 21

“Perhaps they had stolen a monstrance to run away with it and sell it somewhere. That must have been a terrible sin, to go in there quietly at night, to open the dark press and steal the flashing gold thing into which God was put on the altar in the middle of flowers and candles at benediction while the incense went up in clouds at both sides as the fellow swung the censer and Dominic Kelly sang the first part by himself in the choir. But God was not in it of course when they stole it. But still it was a strange and a great sin even to touch it.” . 40

Monstrance

“The word was beautiful: wine. It made you think of dark purple because the grapes were dark purple that grew in Greece outside houses like white temples. But the faint smell off the rector’s breath had made him feel a sick feeling on the morning of his first communion.” p. 41

“-Where did you break your glasses? repeated the prefect of studies.

-The cinderpath, sir.

-Hoho! The cinderpath! cried the prefect of studies. I know that trick.

Stephen lifted his eyes in wonder and saw for a moment Father Dolan’s whitegrey not young face, his baldy whitegray head with fluff at the sides of it, the steel rims of his spectacles and his no-coloured eyes looking through the glasses. Why did he say he knew that trick?

-Lazy idle little loafer! cried the prefect of studies. Broke my glasses! An old schoolboy trick! Out with your hand this moment!” p. 44

“A hot burning stinging tingling blow like the loud crack of a broken stick made his trembling hand crumple together like a leaf in the fire” p. 44

“Stephen knelt down quickly pressing his beaten hands to his sides. To think of them beaten and swollen with pain all in a moment made him feel so sorry for them as if they were not his own but someone else’s that he felt sorry for.” p. 45

“He saw the rector sitting at a desk writing. There was a skull on the desk and a strange solemn smell in the room like the old leather of chairs.

His heart was beating fast on account of the solemn place he was in and the silence of the room: and he looked at the skull and at the rector’s kind-looking face.” p. 50

“He would be very quiet and obedient: and he wished that he could do something kind for him to show him that he was not proud.” p. 53

“Stephen knelt at his side respecting, though he did not share, his piety. He often wondered what his granduncle prayed for so seriously. Perhaps he prayed for the souls in purgatory or for the grace of a happy death or perhaps he prayed that God might send him back a part of the big fortune he had squandered in Cork.” p. 56

“Trudging along the road or standing in some grimy wayside public house his elders spoke constantly of the subjects nearer their hearts, of Irish politics, of Munster and of the legends of their own family, to all of which Stephen lent an avid ear.” p. 56

“The hour when he too would take part in the life of that world seemed drawing near and in secret he began to make ready for the great part which he felt awaited him there nature of which he only dimly apprehended.

His evenings were his own; and he pored over a ragged translation of The Count of Monte Cristo. The figure of that dark avenger stood forth in his mind for whatever he had heard or divined in childhood of the strange and terrible.” p. 56

“Outside Blackrock, on the road that led to the mountains, stood a small whitewashed house in the garden of which grew many rosebushes: and in this house, he told himself, another Mercedes lived. Both on the outward and on the homeward journey he measured distance by this landmark: and in his imagination he lived through a long train of adventures, marvellous as those in the book itself, towards the close of which there appeared an image of himself, grown older and sadder, standing in a moonlit garden with Mercedes who had so many years before slighted his love, and with a sadly proud gesture of refusal, saying:

-Madam, I never eat muscatel grapes.” p. 57

To read:

Dantès sur son rocher, affiche de Paul Gavarni pour Monte Cristo d’Alexandre Dumas. 1846.

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

“He passed unchallenged among the docks and along the quays wondering at the multitude of corks that lay bobbing on the surface of the water in a thick yellow scum, at the crowds of quay porters and the rumbling carts and the ill dressed bearded policemen. The vastness and strangeness of the life suggested to him by the bales of merchandise stocked along the walls or swung aloft out of the holds of streamers wakened again in him the unrest which had sent him wandering in the evening from garden to garden in search of Mercedes.” p. 60-61

“He sat listening to the words and following the ways of adventure that lay open in the coals, arches and vaults and winding galleries and jagged caverns.

Suddenly he became aware of something in the doorway. A skull appeared suspended in the gloom of the doorway. A feeble creature like a monkey was there, drawn there by the sound of voices at the fire. A whining voice came from the door asking:

-Is that Josephine?” p. 62

To read:

Lord Byron:

Don Juan, Manfred, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Mazeppa, Hebrew Melodies.

The Bride of Abydos or Selim and Zuleika. Painting, 1857, by Eugène Delacroix depicting Lord Byron’s work.

“The light spread upwards from the glass roof making the theatre seem a festive ark, anchored among the hulks of houses, her frail cables of lanterns looping her to her moorings.” p. 69

“Then a noise like dwarf artillery broke the movement. It was the clapping that greeted the entry of the dumb bell team on the stage.” p. 69

“Stephen shook his head and smiled in his rival’s flushed and mobile face, beaked like a bird’s. He had often thought it strange that Vincent Heron had a bird’s face as well as a bird’s name.” p. 70

“-Here. It’s about the Creator and the soul. Rrm… rrm…rrm…Ah! without a possibility of ever approaching nearer. That’s heresy.

Stephen murmured:

-I mean without a possibility of ever reaching.

It was a submission and Mr Tate, appeased, folded up the essay and passed it across to him, saying:

-O…Ah! ever reaching. That’s another story.

But the class was not so soon appeased. Though nobody spoke to him of the affair after class he could feel about him a vague general malignant joy.” p. 73

“As soon as the boys had turned into Clonliffe Road together they began to speak about books and writers, saying what books they were reading and how many books there were in their father’s bookcases at home. Stephen listened to them in some wonderment for Boland was the dunce and Nash the idler of the class. In fact after some talk about their favourite writers Nash declared for Captain Marryat who, he said, was the greatest writer.

-Fudge! said Heron. Ask Dedalus. Who is the greatest writer, Dedalus?

Stephen noted the mockery in the question and said:

-Of prose do you mean?

-Yes.

-Newman, I think.

-Is it Cardinal Newman? asked Boland.

-Yes, answered Stephen.” p. 74

To read:

John Henry Newman

The Dream of Gerontius, Apologia Pro Vita Sua.

Naval officer and writer Frederick Marryat

See: Confiteor

“-Admit that Byron was no good.

-No.

-Admit.

-No.

-Admit.

-No. No.

At lasty after a fury of plunges he wrenched himself free. His tormentors set off towards Jone’s Road, laughing and jeering at him, while he, half blinded with tears, stumbled on, clenching his fists madly and sobbing.” p. 76

“While his mind had been pursuing its intangible phantoms and turning in irresolution from such pursuit he had heard about him the constant voices of his father and of his masters, urging him to be a gentleman above all things and urging him to be a good catholic above all things. These voices had now come to be hollow sounding in his ears.” p. 77

“He gave them ear only for a time but he was happy only when he was far from them, beyond their call, alone or in the company of phantasmal comrades.” p. 78

“He stood still and gazed up at the sombre porch of the morgue and from that to the dark cobbled laneway at its side.” p. 80

“-That is hose piss and rotted straw, he thought. It is a good odour to breathe. It will calm my heart. My heart is quite calm now. I will go back.” p. 80

****”As the train steamed out of the station he recalled his childish wonder of years before and every event of his first day at Clongowes. But he felt no wonder now. He saw the darkening lands slipping away past him, the silent telegraphpoles passing his window swiftly every four seconds, the little glimmering stations, manned by a few silent sentries, flung by the mail behind her and twinkling for a moment in the darkness like fiery grains flung backwards by a runner.” p. 81

“He listened without sumpathy to his father;s evocation of Cork and of scenes of his youth-a tale broken by sighs or draughts from his pocket flask whenever the image of some dead friend appeared in it, or whenever the evoker remembered suddenly the purpose of his actual visit.” p. 81

“They drove in a jingle across Cork while it was still early morning and Stephen finished his sleep in a bedroom of the Victorian Hotel.” p. 81

“His father was standing before the dressingtable, examining his hair and face and moustache with great care, craning his neck across the water jug and drawing it back sideways to see the better. While he did so he sang softly to himself with quaint accent and phrasing:

“‘Tis youth and folly

Makes young men marry,”” p. 82

“The consciousness of the warm sunny city outside his window and the tender tremors with which his father’s voice festooned the strange sad happy air, drove off all the mists of the night’s ill humour from Stephen’s brain.” p. 82

“Then he had been sent away from home to a college, he had made his first communion and eaten slim jim out of his cricket cap and watched the firelight leaping and dancing on the wall of a little bedroom in the infirmary and dreamed of being dead, of mass being said for him by the rector in a black and gold cope, of being buried then in the little graveyard of the community off the main avenue of lines. But he had not died then. Parnell had died.” p. 86-87

River Lee (Cork)

River Liffey (Dublin)

“His mind seemed older than theirs: it shone coldly on their strifes and happiness and regrets like a moon upon a younger earth. No life or youth stirred in him as it had stirred in them.” p. 89

“His childhood was dead or lost and with it his soul capable of simple joys and he was drifting amid life like the barren shell of the moon.

“Art thou pale for weariness

Of climbing heaven and gazing on the earth,

Wandering companionless?…” p. 89

To read:

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Prometheus Unbound, Ozymandias, Ode to the West Wind, To a Skylark, Music, When Soft Voices Die, The Cloud, The Masque of Anarchy.

Louis Édouard Fournier, The Cremation of Percy Bysshe Shelley, oil on canvas, Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery. Louis Édouard Fournier (1857-1917). Via Wikimedia.