McCarthy, Cormac. The Orchard Keeper. New York, N.Y.: Vintage International, 1993. Print. (First ed. 1965).

“A phantom rabbit froze in the headlights, rolled one white eye, was gone.” p. 20

“One by one the fallen were entering through the front door red with blood and clay and looking like the vanquished in some desperate encounter waged with sabers and without quarter.” p. 26

“For miles on miles the high country rolled lightless and uninhabited, the road ferruling through dark forests of owl trees, bat caverns, witch covens.” p. 31

“Above the heads of the dancers he could see himself hollow-eyed and sinister in the bar mirror and it occurred to him that he was ungodly and tired.” p. 32

“Cabe made off with a cashbox and at the last minute authorized the fleeing patrons to carry what stock they could with them, so that with the warmth of the fire and the bottles and jars passing around, the affair took on a holiday aspect.” p. 47

“By now the entire building was swallowed in flames rocketing up into the night with locomotive sounds and sucking on the screaming updraft half-burned boards with tremendous velocity which fell spinning, tracing red ribbons brilliantly down the night to crash into the canyon or upon the road, dividing the onlookers into two bands, grouped north and south of harm’s way, their faces lacquered orange as jackolanterns in the ring of heat.” p. 47-48

“There it continued to burn, generating such heat that the hoard of glass beneath it ran molten and fused in a single sheet, shaped in ripples and flutings, encysted with crisp and blackened rubble, murrhined with bottlecaps. It is there yet, the last remnant of that landmark, flowing down the sharp fold of the valley like some imponderable archeological phenomenon.” p. 48

“Coming back he glanced down at the water again. The thing seemed to leap at him, the green face leering and coming up through the lucent rotting water with eyeless sockets and green fleshless grin, the hair dark and ebbing like seaweed.” p. 54

***”She told him that the night mountains were walked by wampus cats with great burning eyes and which left no track even in snow, although you could hear them screaming plain enough of summer evenings.” p. 59-60

“In the fall before this past winter he had come awake one night and seen it for the second time, black in the paler square of the window, a white mark on its face like an inverted gull wing. And the window frame went all black and the room was filling up, the white mark looking and growing. He reached down and thumbed the hammer and let it fall. The room erupted… he remembered the orange spit of flame from the muzzle and the sharp smell of burnt powder, that his ears were singing and his arm hurt where the butt came back against it.” p. 60

“The well hidden in the weeds and johnson grass that burgeoned rankly in the yard had long shed its wall of rocks and they were piled in the dry bottom in layers between which rested in chance interment the bones of rabbits, possums, cats, and other various and luckless quadrupeds.” p. 63

(young rabbit in the well) “He brought green things to it every day and dropped them in and then one day he futtered a handful of garden lettuce down the hole and he remembered how some of the leaves fell across it and it didn’t move. He went away and he could see for a long time the rabbit down in the bottom of the well among the rocks with the lettuce over it.” p. 64

describing a market “By shoe windows where shoddy footgear rose in dusty tiers and clothing stores in whose vestibules iron racks stood packed with used coats, past bins of socks and stocking, a meat market where hams and ribcages dangled like gibbeted miscreants and in the glass cases square porcelain trays piled with meat white-spotted and trichinella-ridden, chinks of liver the color of clay tottering up from moats of water blood, a tray of brains, unidentifiable gobbets of flesh scattered here and there.” p.82

“And the sun running red on the mountain, high killy and stoop of a kestrel hunting, morning spiders at their crewelwork. But no muskrats struggled in his sets.” p. 87

“The old man remembered it now with dim regret. and remembered such nights when the air was warm as breath and the moon no dead thing.” p. 89

“The moon was higher now as he came past the stand of bullbriers into the orchard, the blackened limbs of the trees falling flatly as paper across the path and the red puddle of moon moving as he moved, sliding sodden and glob-like from limb to limb, flatly surreptitious, watching as he watched.” p. 89

“The glade seemed invested with an aura of antiquity, overhung with a silence both spectral and reverent.” p. 90

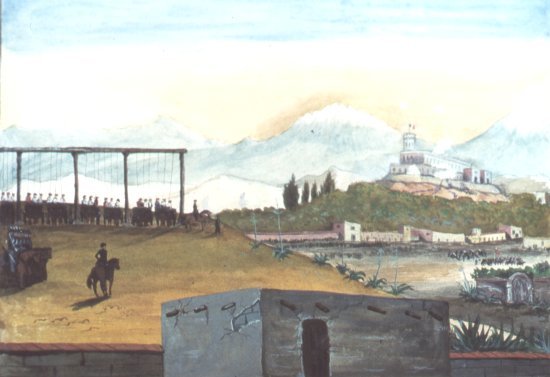

***”And on the very promontory of this lunar scene the tank like a great silver ikon, fat and bald and sinister.” p. 93

“But there was the house looming, taking shape as he approached, and he felt that he had come a great distance, a sleepwalker who might have spanned vast and dangerous terrains unwittingly and unharmed.” p. 93

“He dropped the lid of the locker closed and the lamp flickered, on the wall a black ghoul hulking over a bier wavered.” p. 94

“The bottle clattered on the floor, he lurched once, wildly, collapsed into the bread rack and went to the floor in a cascade of cupcakes and moonpies.” p. 96

“Wiping water from his eyes he looked about and saw the flashlight, still lit, scuttling downstream over the bed of the creek like some incandescent water-creature bent on escape.” p. 100

“They paid little attention to him and he just watched them, the injured man waving his arms, telling the story, the other scratching alternately belly and head and saying Godamighty softly to himself from time to time by way of comment.” p. 105

“Mornin, the man said cheerfully.

Are you hurt? she asked. She was small and blond and very angry-looking.” p. 107

“The boy looked down at himself, soggy and mudsplattered, seeds and burrs collected on his waterdark jeans like some rare botanical garden being cultivated there, at his rubber kneeboots with twigs and weeds sticking out of them,” p. 108